Every woman can relate to John Proctor is the Villain, and that’s why every man should see it too

- Ariana Glaser

- Jul 3, 2025

- 5 min read

Updated: Jul 27, 2025

Kimberly Belflower’s John Proctor is the Villain redefines Arthur Miller’s The Crucible in the context of a 2018 high-school classroom.

Right at the heart of the #MeToo movement, four eleventh-grade girls form a feminism club to discuss the story and how it relates to their everyday lives. While their female guidance counselor (Bailey Gallagher, portrayed by Molly Griggs) suggests the club is poorly timed with everything going on in the world, the girls’ male English teacher (Carter Smith, portrayed by Gabriel Ebert) green lights the group and agrees to be their faculty advisor. The founding members include Beth Powell (Fina Strazza), Raelynn Nix (Amalia You), Ivy Watkins (Maggie Kuntz) and Nell Shaw (Morgan Scott).

Their discussions begin lighthearted as they contemplate sex, relationships, and female characterizations both in the contexts of The Crucible and their own lives. Tensions rise and their discussions become more and more relevant as Ivy’s father is accused of sexual harassment and Raelynn’s estranged friend Shelby (Sadie Sink) returns to school after a prolonged absence and soon after reveals that she and Mr. Smith had engaged in a sexual relationship. The school district’s reaction enrages the students—and the audience—though it deepens the sting of the story all the more. Mr. Smith is not fired; instead, Shelby is removed from his class. She does, however, get to perform an epic interpretive dance to Lorde’s “Green Light” alongside Raelynn right in Mr. Smith’s face before departing. Throughout the song, the other girls join in, and together they dance, they destroy, and they heal. Ms. Gallagher, who alludes to the idea that she’d heard rumors that Mr. Smith might be a predator several years ago but dismissed them, physically keeps him from halting their performance.

The play’s foundation centers around the idea of refocusing the blame from Abigail Williams to John Proctor, to reframing the latter from his original title as hero to hunter. Just before Shelby reveals her big secret, Mr. Smith paints John Proctor as one of the greatest heroes in literature, and it makes sense that he’d think so. So similarly to Goody Proctor, Mr. Smith was married and his wife was pregnant. It would stand to reason that Mr. Smith sees himself as a weak man rather than a powerful predator, and he sees Shelby as a vengeful siren rather than a victim.

It’s admittedly been several years since I’ve read The Crucible, but as history retells the Salem Witch Trials, the town preyed on the idea of feminine hysteria, sorting through it all to cleanly decide on witchcraft as the only presumable explanation. When Abigail and her friends dance naked in the forest, they’re accused of witchcraft when in all actuality they’re just being children—children forced into a world far older than them, a world where they must run to the forest for a single moment of freedom.

John Proctor, however, was one of the few characters in the play who didn’t believe in witchcraft—therefore whether outwardly or not, Proctor admits his own fault in his affair. He acts willingly, not by the hands of any external force. Still, in open words he places all blame on Abigail, calling her a “whore” and deeming her “suspicion” as the cause for tension in his marriage. When judgement day comes along, John Proctor recites his epic confession, “I have given you my soul; leave me my name,” as a final emblem of his regard for his own honor above all else, owing nothing at all to the fact that it was he and he alone who rid himself of that honor in the first place.

The everlasting story of the man placing the blame on the girl comes back full-swing with Mr. Smith’s sexual assault of Shelby.

And it is sexual assault—the truth in the matter rests within the fact that Shelby, like her literary counterpart, is sixteen—and though sexual ethics and legalities were not nearly as outlined in the 1600s as they are now, by the era of JPTV it is undeniable that Shelby is under the age of consent, and Mr. Smith is in a position of power over her.

Whether Shelby consented or not is irrelevant, and Mr. Smith’s sad soliloquy toward the end of the play where he admits he knew Shelby had a crush on him and regrets not putting a stop to things sooner goes to show that in the end he is the adult and she is the child. He took advantage of her, and it’s unfortunate that he like so many other sexual predators gets to walk free, that he like so many other sexual predators gets to be named a martyr while the girl he raped is deemed insane.

We know Mr. Smith suffers little consequences for his actions. He remains a teacher (which warrants a whole separate conversation about how easily pedophiles find their way into careers centering around children, but I digress), and it’s Shelby who’s required to uproot her education for the second time. We know Mr. Smith has had other victims in the past. We know he’d likely have tried to seduce other children (see: his strange ‘friendship’ with teachers’ pet Beth who only finally realizes at the eleventh hour that Shelby was telling the truth and that Mr. Smith is not the man she trusted) if it weren’t for Shelby calling his bluff.

Too often the men we trust are the men who turn around and betray that trust in the worst way possible. While men criticize women for their apprehension to meet them in private places on a first date or vehemently object the “man or bear” trend (an idea in which women suggest they’d feel safer alone with a bear than with a man), it’s stories like these that should emphasize why women are fearful.

There’s an old adage I heard once that compared the idea to Russian roulette—a lethal game of chance. The idea goes that while we understand it’s not all men, we can’t simply take the risk of letting our guard down around men. The consequences are too great, and the number of horror stories too large.

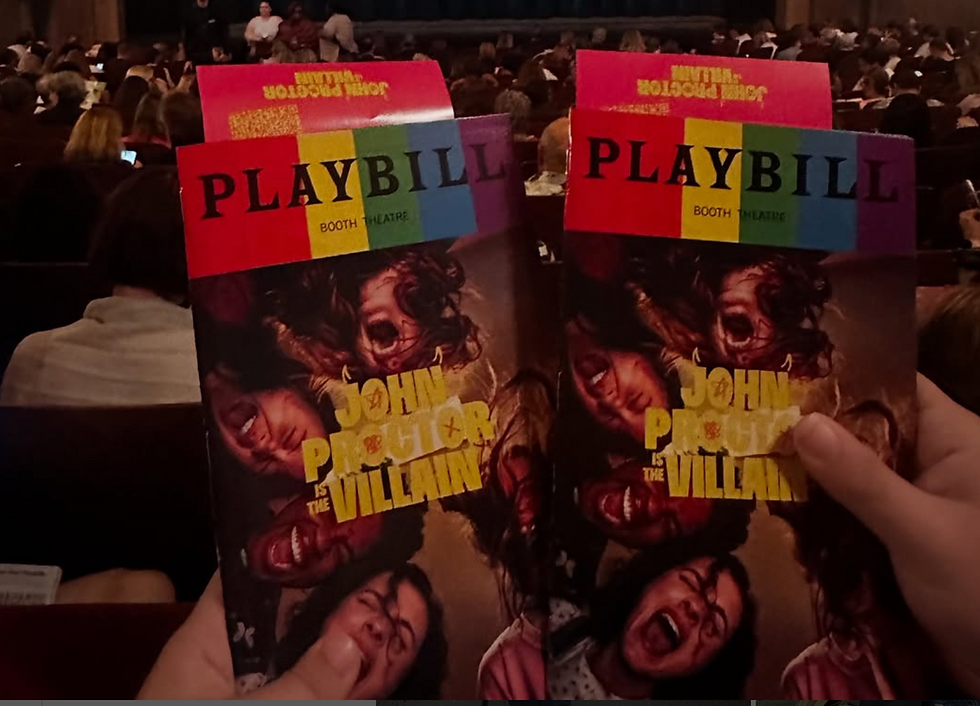

Outside the theatre, several women could be seen carrying their playbills while wiping away tears: because it’s not all men, but it’s most woman.

Comments