White coats and red hands: How institutional and legal failures enable sex abuse in medicine

- Ariana Glaser

- Jul 22, 2025

- 7 min read

Updated: Jul 27, 2025

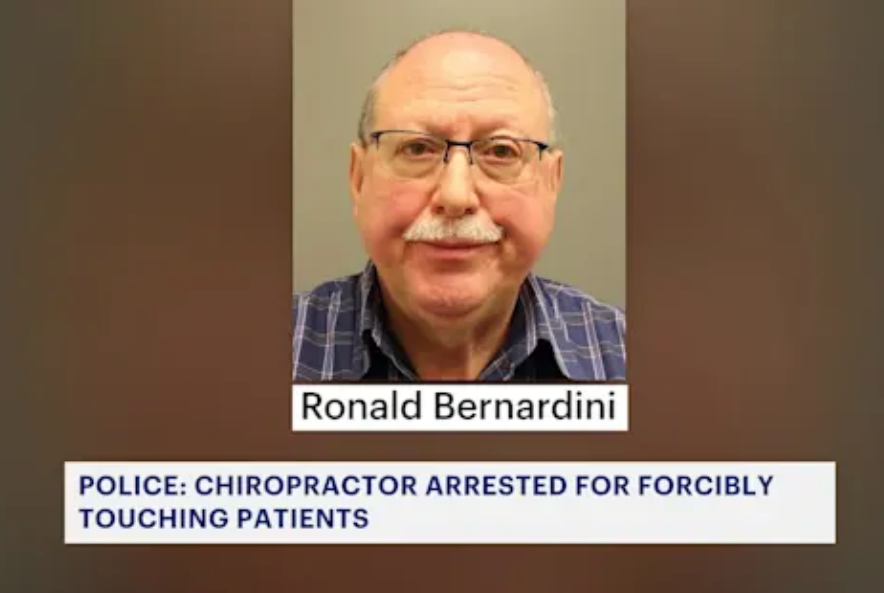

When I was sixteen, my father took me to Lake Chiropractic in Ronkonkoma, New York. With my father in another room and the door closed, Dr. Ronald Bernardini asked invasive, inappropriate questions—none of which had anything to do with the back pain for which I’d come in.

Then he ran his hands over my breasts.

It wasn’t until after I came forward that other victims did too. Our combined testimonies led to a Class A misdemeanor conviction and the revocation of his license to practice. After the trial, I couldn’t help but feel a bit melancholy as I wondered: What would have happened if I hadn’t been believed?

I knew what would have happened, of course. He would have continued to use his prowess as a man in a position of power, and not just any position of power—a position which quite literally requires victims to put an autonomic, intimate level of trust into his hands. Dr. Ronald Bernardini was able to practice for forty years, and while I may have been his last victim, I was far from the first or last woman to be harmed in what’s meant to be a healing space. Institutional coverups and gaps in legal protections are paramount in allowing red-handed predators in white coats to keep acting.

By definition, medical malpractice is an all-encompassing term. The National Institutes of Health defines medical malpractice as “any act or omission by a physician during treatment of a patient that deviates from accepted norms of practice in the medical community and causes an injury to the patient.”

Most claims are filed involving acts of negligence—misdiagnosis, surgical errors, or improper medication. Far less exploited are the all-too-common instances where instead of healing patients, physicians use their position to satisfy their own wicked ideals. In these situations, malpractice isn’t by mistake—it’s by betrayal.

We tend to picture a sexual predator as a hooded man in an alleyway, a drunk frat brother at a college party, or a manipulative professor. Rarely do we concoct the image of a predator in a white coat, but sexual abuse by medical professionals is more common than most realize.

An Atlanta Journal-Constitution study found that between 1999 and 2016, more than 3,100 doctors were publicly disciplined after being accused of sexual infractions. This figure neglects to account for the much higher number of people whose stories remain unheard and whose assailants walk free. In fact, New York State public records revealed that between 2007 and 2018, only 4% of medical sex abuse complaints ended in board actions.

Particularly when victims aren’t aware of the full extent of their condition or the necessities involved with their procedure, doctors are able to trick patients into undergoing care that is truly just means for achieving their own sexual gratification.

A college student in her early twenties who wished to remain anonymous was referred to a GI doctor for strong stomach pain, and this same doctor informed her that he would need to conduct a pelvic exam to “rule some things out.”

Though the beginning of the exam offered nothing out of the ordinary, it was when the doctor ordered the nurse out of the room that things took a turn for the worse.

“And that’s when he assaulted me,” she recounted. “With an object, with his fingers and orally, both vaginally and on my chest.”

Though the survivor didn’t immediately tell anyone about her experience, she admitted to being apprehensive when confronted with the need to go to medical appointments in the future.

“I hated doctors and wanted nothing to do with them,” she said. “I ended up getting hurt at work and had to go to the ER…[I] almost had a panic attack.”

The unique dilemma of sexual abuse in the medical field? It’s often difficult to discern whether there might have been a valid reason for whatever the doctor insisted was necessary. Oftentimes, by the time victims come to terms with their trauma, the Statute of Limitations is up. In New York State, medical malpractice victims have a mere 30 months to file a civil lawsuit.

After that, their story is null and void.

Ali Cirile, a second-year masters student at the University of Miami, remembered being required to take her underwear off at a routine checkup when she was just six years old.

“I started screaming and crying and trying to fight him off,” said Cirile. “He didn’t even do any kind of vaginal exam…[he] just looked at my vulva and then had me pull my pants up.”

Even her mother later realized it was strange since there were no prior health concerns which might have required such an uncomfortable examination. For several years after the incident, Cirile felt as though she had “no control” over her anatomy or who got to “see and touch” her while she was naked.

Stories like Cirile’s reveal just how easily doctors can weaponize their authority.

One of the most prominent examples is USA gymnastics team physician Larry Nassar, whose conviction was amongst the biggest sex scandals in sports history. His history of treating Olympic athletes made him a highly coveted doctor; parents were told their children should be “honored” if Dr. Nassar would treat them. It was his elevated position that allowed him to sexually assault hundreds—possibly thousands—of young athletes, several of which were minors.

When this all came to light, the world’s first question was: How? How could this have happened? The ultimate truth is that doctors are meant to be trusted. When Dr. Nassar insisted that it was positively necessary to conduct wholly unsupervised pelvic exams in his victims’ hotel rooms or dorm beds, no one batted an eye. He knew best. He had the degree and the reputation to precede him.

Institutional coverups are often to blame for why those abusing their power are able to continue doing so for such a long time, but legalities don’t play a fair role in protecting victims either.

Most states do not have a law specifically criminalizing “sexual abuse by a healthcare provider,” and there are no laws whatsoever requiring a parent to be present in the room for a minor’s care.

In 2018, the Los Angeles Times exposed the University of Southern California for allowing George Tyndall, the only full-time gynecologist, to abuse women for three decades. Allegations of sexual misconduct began in 1997 when coworkers accused him of improperly photographing patients’ genitals. In the years that followed, Tyndall continued to take lewd pictures of students, make inappropriate comments and occasionally use his fingers to supposedly stretch the vaginal muscle before inserting the speculum.

The University quietly offered Tyndall the opportunity to resign quietly while granting him a financial payout. After Tyndall accepted, the University neither informed his patients nor reported him to the Medical Board of California. U.S.C. prioritized avoidance of scandal over protection of students at terrible cost to the latter. It was only when the story broke out on a national scale that Tyndall was faced with criminal charges and the University paid $1.1 billion in settlements to his victims.

Several of Tyndall’s victims came out about their experience years later, explaining that they convinced themselves that they had misunderstood the situation. He was employed by the University for thirty years—surely action would have been taken previously if he was someone to fear?

“I was telling myself, ‘You’re just being sensitive…he’s a professional. He’s not going to do anything weird,’” recounted one USC student.

What Drs. Nassar and Tyndall’s stories have in common is simple—the abusers were protected first. The structures meant to hold doctors accountable instead allowed their lewd behavior to continue, whether with regard to protecting the institutions which housed them, by the disbelief that a widely trusted doctor would act against his or her profession, or by undeterrable negligence. Only after major news outlets revealed the true happenings at their hands were they finally stopped.

There’s certainly been progress. Under federal law enacted in 2018, all U.S. Olympic sports officials are mandated reporters of child abuse. This is due in part to USA Gymnastics’ handling of the Dr. Nassar situation—particularly their decision to investigate the matter internally and quietly.

But even when reports are filed, there’s been a harsh pattern of leniency by state medical boards. A new AJ-C investigation uncovered 450 cases of doctors brought before regulators or judges for sex crimes in 2016 and 2017. In most cases, doctors are permitted to maintain their practice while investigation is ongoing. In nearly half of those cases, the doctors were still permitted to practice.

And in the rare instances doctors do lose their license to practice in one state, they’re often able to obtain licensure in another due to limited information shared between medical boards or variations in state laws. Then comes the dilemma of patients unknowingly walking themselves right into the lion’s den—while some states have enacted laws requiring doctors to disclose any malpractice settlements or criminal convictions on a public forum (for example, California’s 2018 “Patient’s Right to Know Act”), most states have no legal disclosure requirements.

When the story of my own sexual assault reached the media, hecklers took to the internet to claim I’d made a false allegation for monetary benefits. People are quick to protect doctors because doctors are meant to protect their patients.

When you go to a medical appointment, you’re putting your health, your body, and your trust into someone else’s hands. For me and so many other unsung survivors, that trust was exploited.

While it’s true that most doctors’ first instinct is “do no harm,” those whose primal instincts are far more sinister must be adequately disciplined.

Place doctors on administrative leave during investigations. Require a chaperone (i.e. a nurse or parent) for sensitive exams. Don’t allow a convicted perpetrator to continue practicing in another state. Enforce strict boundaries in doctor-patient relationships—and impose serious penalties when those boundaries are crossed.

Survivors’ lives are forever impacted. Perpetrators should not be allowed to continue theirs without being held accountable—least of all in exam rooms, with unrelenting access to more potential victims.

Comments